Photographs, Pistols, and Parasols

P3-003 The Mad Tea Party

LISTEN

The Wonderfully Mad World of Hannah Maynard

View Transcript

——————————————————————————————————————————————

Snapsheet

Photographer: Hannah Maynard

Dates: 1834 (Cornwall, England) -1918 (Victoria, Canada)

Active: 1862-1912 (Victoria, Canada)

Ran Studio? Yes

Known for: Portraits, Landscapes, Collages, Police Department Mugshots

More Information

All of the images below are from the Royal BC Museum Archives in Victoria, BC, Canada. Click on an image to see its entry in the archve’s database. Note that the titles in [] are unofficial ones I have assigned for reference.

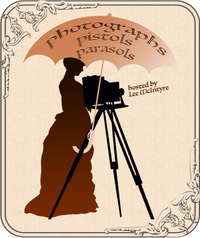

Hannah Maynard, [The Unexpected Tea Party], ca.1893

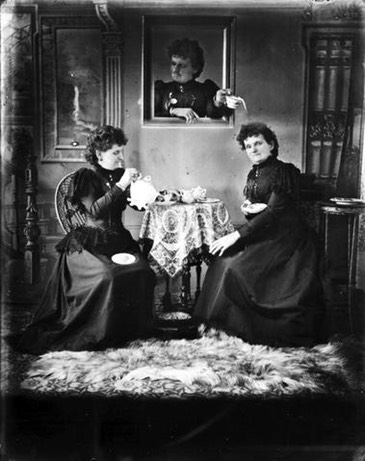

Hannah Maynard, [In a Victorian Parlor], ca.1895

Hannah Maynard, [Surreal Family Tableau], ca.1895

Hannah Maynard, [Hannah her grandson and the locust], ca.1895

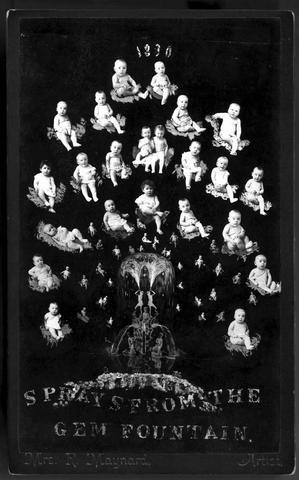

Hannah Maynard, "Sprays from the Gem Fountain" (print), ca.1880-1890 (in the fountain toward the bottom there are faces flowing in the water and reflected in the “pool” of water below.

Hannah Maynard, "Sprays from the Gem Fountain” (glass plate negative), ca.1880-1890

——————————————————————————————————————————————

Transcript

Welcome to Photographs, Pistols, and Parasols, the podcast that celebrates the wit wisdom and élan of early women photographers.

I'm your host, Lee McIntyre.

In today's episode I'm going to take you to the slightly surreal world of nineteenth century photographer Hannah Maynard.

More information about any of the materials discussed in today's snapsheet can be found on my website, at p3podcast.clfoto.net, that's P, number 3, podcast dot C L F O T O.net.

In today's snapsheet you're invited to a slightly surreal tea party as we explore the experimental photography of 19th century photographer Hannah Maynard.

Hannah Maynard was born in England, but she moved to eastern Canada in the 1850s when her husband decided to move the family there so he could open up a shoe business in eastern Canada.

He later got gold fever and left Hannah Maynard and the kids in eastern Canada while he went west to see what fortunes he could find.

While she was alone with the children, Hannan took herself off to a photography studio and asked the photographer to teach her how to be a studio photographer. So, by the time her husband came back and announced that the family would be moving to Victoria in British Columbia, well, Hannah Maynard had made up her mind to become a photographer.

In 1862 she opened up a studio in Victoria, British Columbia, that she ran for the next fifty years.

She was very successful doing both landscape photography as well as a lot of studio photography. Her specialty in the beginning was really taking images of children, and she photographed children in that town, as I said, for fifty years.

Even though she was doing studio photos which were of a particular type, she was experimenting in ways that other photographers didn't do: incorporating mirrors into her photos early on, taking reflections of the people but also using mirrors to represent water; posing the children as though they were at the edge of a pond in the middle of a forest, using backdrops to illustrate the forest and the mirrors to illustrate the water.

She used a variety of equipment and techniques over the years. In the 1880s she used a style called Gem photography, which was a very particular small scale photo that allowed you to put it easily into a piece of jewelry, like a locket or something like that.

Not only did she market these kinds of images for jewelry, she also used them for yearly advertising for her business in the 1880s, creating something she called the Gems of British Columbia. These are collages that are creative montages of all the images of the children that she'd taken during the previous year, but arranged in some sort of scene or depiction of an object. For example, the year of the queen's jubilee in the mid 1880s, Hannah Maynard takes all of the images that she take in that year and arranges all of the faces in the shape of the queen's crown.

She also has images where there's a fountain and the children's faces are flowing out of the water of the fountain. She incorporates the idea of the mirrored images creating reflections of the children seated by the water. This is all done in the darkroom, painstakingly constructing these montages year after year, and incorporating the previous year's montage [as well], so at the end of ten years her final montage, her final Gem of British Columbia, contains twenty two thousand images of children.

Now in the 1890s she starts to experiment more with multiple exposures, some of which are slightly surreal. I think my favorite photo is really one that I call the "Mad Tea Party". Now when you look at it a quick glance, it looks like it's the depiction of three women having a tea party in a 19th century Victorian parlor:

- There's a woman on the left-hand side pouring the tea,

- There's a woman on the right-hand side holding a teacup, and

- There's a woman in the middle of the table.

But then we realize, well — wait, that woman in the middle, she's not actually *at* the table, she's in a photo that's framed *above* the table that's hanging on the wall.

But she's not just *in* the frame, she's actually leaning *out* of the frame. She's got a teacup at her hand, and she is dumping the contents of her teacup on the woman who is seated at the right hand side of the table.

That's all surreal enough, but then you realize that all three of the women are Hannah Maynard herself. She has taken three images of herself and incorporated them seamlessly into this image that seems to show three women at the same table.

It's really amazing. I mean you can do multiple exposures today on the computer in the "digital darkroom," but it's hard to actually manipulate them so that they're seamlessly integrated. The lighting has to be just right or you have to manipulate them just so. On a computer that's hard to do, and so I really tip my hat to Hannah Maynard for doing this so well in the darkroom in the 1890s.

Now in the late 1890s, Hannah Maynard goes to work to become the official Victoria police department photographer, where she's responsible for taking mug shots of the people under arrest. And so she devises a particular style of mugshot using a mirror, where in a single image she's able to take not just the full view of the face but also the profile, in one image, saving film and saving time when taking the images. It's an innovation that unfortunately doesn't seem to have been picked up by other police photographers, but it really was something that Hannah Maynard contributed to the field back then.

Now, I have seen her mentioned in a couple of books on women photographers, but I hadn't ever seen anything about her cleverness and such creativity until I ran across a book called "The Magic Box". And I really want to recommend that if you can find a copy of that book, it has a lot more examples of her cleverness and her creativity, and the way in which she was able to go beyond the boundaries of photography in late 1800s and really see what photography could be all about.

So we think about doing creative things with our images — taking selfies, doing things in Instagram — we can actually learn a lot from looking back to see what Hannah Maynard was able to do back in the 19th century.

Now in the show notes for today's episode, I'll include not only a copy of that "Mad Tea Party" photo I described, but also some more of Hannah Maynard's multiple exposure works, so you can see just how surreal she got there in the 1890s.

All this will be available on my website at p3.clfoto.net, that's letter p, number 3, dot clfoto.net.

Well that's it for today. Thanks for stopping by. My name's Lee McIntyre, and this is Photographs, Pistols, and Parasols.

P3-002 Petticoats and Parasols

LISTEN

EIlizabeth Withington and her photographic petticoats and parasols

View Transcript

——————————————————————————————————————————————

Snapsheet

Photographer: Elizabeth Withington

Dates: 1825 (USA) -1877 (USA)

Active: 1852-1877 in California

Ran Studio: Yes

Known for: Portraits and Landscapes

Links

- Materials on Women in Photography Archive website

- Essay by photo historian Peter Palmquist that also includes the full text of Elizabeth Withington’s 1876 article, How a Woman Takes Landscape Photographs

- Bibliography for books and articles about Elizabeth Withington

- Another short essay about Elizabeth Withington, also written by photo historian Peter Palmquist for the Clio Visualizing History website. This page includes several photos attributed to Elizabeth Withington.

- The short biographic sketch on the Historic Camera website that includes a list of places that have some of of Elizabeth Withington's photographs.

Notes

- I first ran across Elizabeth Withington when reading Peter Palmquist's excellent book, Camera Fiends and Kodak Girls, which offers a good selection of essays and articles written in the 1800s by and about women photographers. A highly recommended read!

- That the name of this podcast is a nod to Elizabeth Withington’s "strong black-linen cane-handled parasol.”

- The Broadway composer Jerry Herman wasn’t writing about a photographer when he wrote his song, A Sensible Woman, but some of the lyrics provide the perfect way to remember Elizabeth Withington:

“… when faced with a problem …with her eye on its target … her parasol brandished, … with wisdom, wit and élan … a sensible woman goes on!” — from the song A Sensible Woman, written by Jerry Herman for the musical Dear World

——————————————————————————————————————————————

Transcript

Welcome to Photographs, Pistols, and Parasols, the podcast that celebrates the wit wisdom and élan of early women photographers.

I'm your host, Lee McIntyre .

Today we'll meet a woman photographer who fashioned clever photography tools out of fashionable nineteenth century women's accessories.

More information about any of the material discussed in today's episode can be found on my website, at p3.clfoto.net. That's P, number 3, c l f o t o .net.

Today I want to tell you about a woman named Elizabeth Withington.

She was a nineteenth century photographer who fashioned clever photography tools of fashionable nineteen century women's fashions.

Let me explain.

Elizabeth Withington was born in 1825, and she opened her first studio in 1857.

She did studio portraits, but by the 1870s she was also becoming noticed for her landscape photos. Now the photos themselves were quite good, but another thing that was attracting attention were rumors about how she was *taking* her landscape photos.

The technology she was using was called wet plate photography, and that was popular for both studio photos as well as for taking landscape photos.

But it was a bit cumbersome because you had to work with the glass plate right after it was coated with liquid, before the plate got dry. It was, after all, called "wet plate photography".

Typically you had no more than ten minutes before the plate would start to dry. Once the photo was exposed, within those ten minutes, you then had to get that plate into a developing solution right away or else the photo would be ruined.

And both the coating of the plate, as well as the developing of the plate, well, those things needed to be done in complete darkness.

So when you look at history books for this period, you'll see mention of the civil war photographers. Now they were using this wet plate photography, and all of the stories about the civil war photographers talk about how when they took their battlefield photos, off on the side of the battlefield would be their dark room wagon, parked ready for them to dash into, in order to develop the image. Because typically photographers doing wet plate photography would have their own darkroom wagon. That was how you had to do it, because you needed a darkroom.

But Elizabeth Withington, well, she was not your typical photographer. A she sort of atypically would travel by public transportation, like stage coach or maybe by hitching a ride on a fruit wagon. Which meant that she would travel without a portable darkroom.

So people wondered, how could she possibly do wet plate photography? I mean, you needed a darkroom.

But Elizabeth Withington was clever. First, she considered the problem of the wet plates. Conventional thinking said you couldn't possibly coat the plates ahead of time because it would dry out too fast.

But she discovered that by carefully wrapping the coated plates in a wet towel she could extend the limit to not just ten minutes, but more like a 180 — three hours worth of time for her to coat them at home and then use them in the field.

So the first problem of needing a darkroom in the field was solved by pre-coating the plates and keeping them wet in that towel.

But then, when she got to her sun-drenched meadow and she took her photo, how in the world was she going to be able to develop the images without having a darkroom at hand?

Once again, an unconventional solution was at hand.

Because Elizabeth Whittington got the idea of taking a dark petticoat, and then turning it into a wearable "darkroom petticoat tent".

She designed it so she could slip it over her head, down to her waist, and then in total darkness be able to apply the developer solution to stabilize the exposed image, so that she could then take it back to her darkroom for final processing.

This was very creative and it allowed her to deal quickly with any of the photos that she took out in the field particularly if she had just stepped off the stage coach and taken a photo. She later wrote that she could do it so quickly that the stagecoach driver wouldn't have to wait extra for her to process her photo.

Now she became famous, as I said, for her photos as well as for her techniques, and in 1876 she was persuaded to write down the details of her techniques in an article that was called "How a woman makes landscape photographs."

In that article she describes how she uses the wet towel and the petticoat darkroom tent as photographers tools for doing landscape photos.

I mentioned a moment ago that what happens if she's standing on the sunlit field when she's taken a photo and she needs to develop it. But she also had a mention in that article of what she would do when there was too much sunlight on her camera. Because she writes about the importance to a woman photographer of a parasol.

Now parasols were common for women to carry in those days. But she says that a woman photographer "needs a strong black-linen, cane-handle parasol" , that's a necessary photographer's tool. Not just for shade for the photographer, but also for improvising a lens shade when you're out in that sun-drenched field and there's just too much light on your lens.

Elizabeth Withington also points out that a parasol can be good for steading yourself as you're walking across rough terrain to get to your photo op. In addition, she comments that it would be useful if you wanted to slide down into a ravine to assess another opportunity for a photo.

Now that's not exactly the standard picture you get when you hear about Victorian ladies with parasols, but that was Elizabeth Withington's advice to women photographers in the Victorian age.

Unfortunately Elizabeth Withington died from cancer at the age of only fifty two in 1877, just a year after her article was published. She was a professional photographer for many years, but there aren't that many of her photographs that have survived to the 21st century. But luckily her legacy is not just in her photographs, but also in her wonderful 1876 article where she explains these tips about using the petticoat and the parasol as photographers tools.

Now nowadays we don't have to really worry about the wet plates and the wet towel, but we still can learn a lot from Elizabeth Withington. Her creativity, resourcefulness, and can do spirit in solving the problems posed by the technology that she was faced with — well that provides inspiration to photographers of any time period.

By the way, the name of my podcast is actually a tribute in-part to Elizabeth Withington , and her advice to women photographers about the use of a strong, black linen, cane-handled parasol.***I'll include a link to the text of her 1876 article in the show notes for this episode. They're located on my website at p3.clfoto.net. That's letter P, number 3, dot C. L. F. O. T. O. dot net.

Well, that's it for today.

Thanks for stopping by, and until next time, I'm Lee McIntyre, and this is Photographs, Pistols, and Parasols.

P3-001 QP: The $100 Photograph

LISTEN

coming soon

Gertrude Käsebier, Pictorialism, and the signficance of the $100 photo

——————————————————————————————————————————————

Snapsheet

Photographer: Gertrude Käsebier

Dates: 1852 (USA) -1934 (USA)

Active: late 1890s - circa 1920

Ran Studio? Yes, in New York City

Known for: Portraits, Pictorialism

QuickPict: The $100 Photograph

Gertrude Käsebier’s pictorialist work, The Manger, 1899:

Gertrude Käsebier’s photo used as the basis for The Manger, 1899:

The first image above is Gertrude Käsebier’s pictorialist image The Manager, a photo that sold for the then-unheard of sum of $100 in 1899. The second image is a scan from the Library of Congress of what is labelled an “experimental negative” version.

Comparing the two images reveals some of the pictorial darkroom “magic” done by Käsebier to create The Manger. Note the softness of the focus, the brightness of the whites, and the adding of shadows around the edges to create almost a vignetting effect. All the changes evoke a dreamy, romanticized mood.

——————————————————————————————————————————————

HTML

Transcript

coming soon

P3-000 Introduction

LISTEN

Introducing Photographs, Pistols and Parasols

View Transcript

——————————————————————————————————————————————

Transcript

Welcome to Photographs, Pistols, and Parasols. I'm your host, Lee McIntyre.

Rudyard Kipling once said, "If history were taught in the form of stories, it would never be forgotten."

I firmly believe that, and so here on this podcast I'm going to share some stories of early women photographers — women who have been nearly forgotten.

We'll meet ...

— a photojournalist who traveled the world in search of stories and photo ops

— a police department photographer who invented a new type of criminal mugshot

— a 19th century itinerant photographer who traveled alone down dangerous roads, her camera equipment always including a pistol tucked in for protection

These are just three of the many women who were successful entrepreneurs running thriving photography businesses starting just after photography began in 1839.

Surprised? You're not alone. Many people mistakenly believe that women became professional photographers only after 1930.

But on this podcast, I'll bring you the fascinating stories of the earlier women professionals. I'll also include a little bit about the technology they worked with, because sometimes it helps to better appreciate the story. I mean you might never have known that circa 1860, if you wanted to do outdoor photography, you had to carry a darkroom in addition to your camera. Once you know that, though, you can better appreciate the cleverness of the landscape photographer who turned her very fashionable 19th century petticoat into a lightweight portable darkroom. She also considered a parasol a necessary photographer's tool.

There will also be also be some companion materials on my website at clfoto.net

So join me to celebrate the unforgettable stories of early women photographers.

Until next time, I'm Lee McIntyre and this is Photographs, Pistols, and Parasols.